NUTRITION CONSULTING INSURANCE COVERED

From strong roots to hardened bark covered trunks that reach upward twisting to the sky where green leaves wave in the wind catching rain drops & sunlight rays to nourish the entire tree. At AVNC we do the same for people by developing firmly rooted plans that nourish strong bodies to help reach fullest potentials.

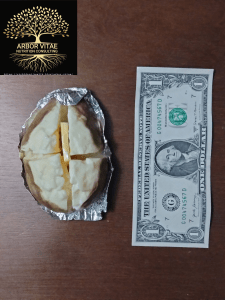

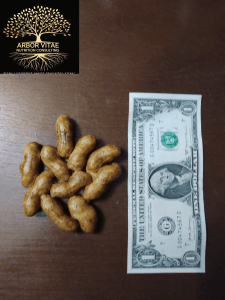

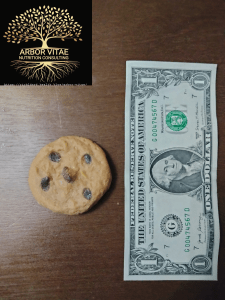

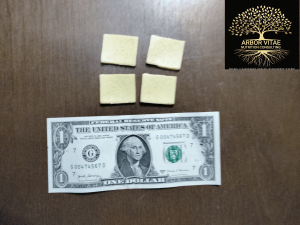

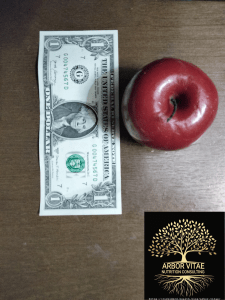

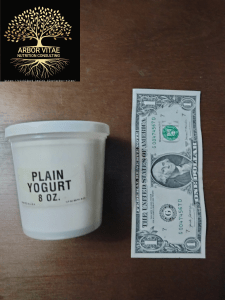

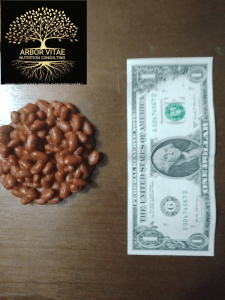

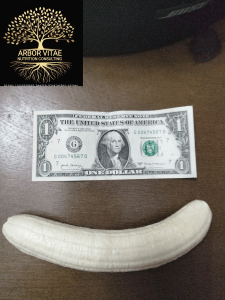

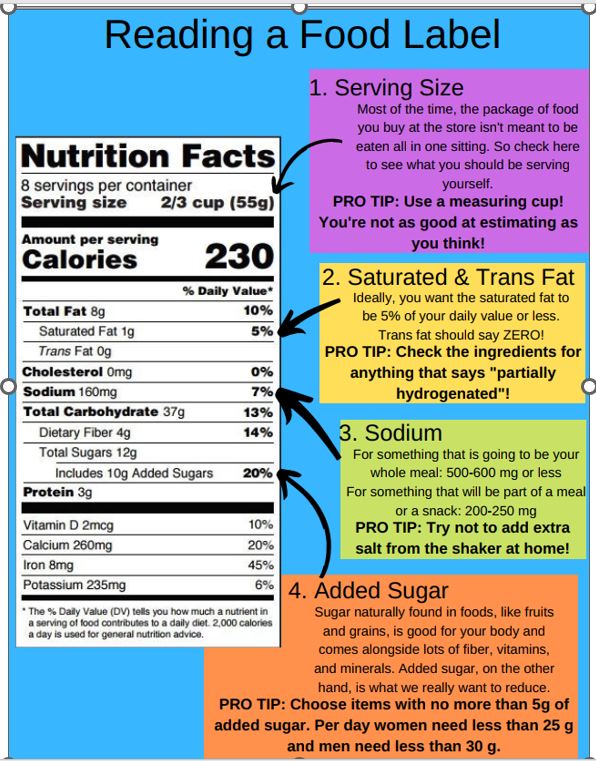

PAY ATTENTION TO YOUR SERVING SIZES!

Serving Size Reality Check?

In our shared human journey, we’ve somehow wandered into a place where feeling overly full has become the unspoken goal of our meals. Let’s take a moment to reflect on this together. The truth is, our bodies thrive on much smaller, yet perfectly nourishing portions than what we’ve come to expect. We’ve been gently nudged, perhaps without even noticing, into believing that the more we eat, the more we’re enjoying life. But, dear friend, there’s a profound beauty in recognizing that true satisfaction comes from what our body truly needs, not from the excess.

When we reach for those packages at the store, we rarely pause to read the whispers of wisdom on the nutrition labels. If we did, we’d discover that what seems like one serving might actually be several, revealing that the calories, the love we give our body through food, are far more than we might have imagined. This realization can be transformative, leading us towards a path of mindful eating where each bite is an act of love and care for ourselves.

We live in a world where our hearts and plates can be full with less, where we can celebrate the joy of eating without the burden of excess. By learning to read and understand those labels, we’re not just feeding our bodies; we’re nurturing our souls with knowledge and respect for our health.

Let’s embrace this shift towards smaller, thoughtful portions, understanding that we’re not being deprived but rather enriched with every mindful choice. This isn’t just about nutrition; it’s about self-care, about honoring our bodies with the right amount of food that fuels not just our physical health but our emotional well-being too. Together, we can foster a culture where eating is an act of joy and balance, where every meal is a celebration of life, health, and the love we have for ourselves and each other.

Metabolism and Calories

Metabolism is the process by which your body converts food and drink into energy to power essential functions like breathing, circulation, cell repair, and maintaining body temperature. This process involves two main parts: anabolism, which builds and repairs tissues and requires energy, and catabolism, which breaks down molecules like fats and carbohydrates to release energy. When you consume more calories than your body needs for immediate use, the excess is stored primarily as fat for later use, a crucial adaptation for survival during periods of food scarcity. The body’s metabolic rate, particularly the basal metabolic rate (BMR), which accounts for 50% to 80% of daily energy expenditure, is influenced by factors like muscle mass, age, genetics, and body size. While the body naturally regulates its metabolism to meet its needs, consuming additional calories can lead to an increase in energy expenditure through the thermic effect of food (TEF), where the body uses energy to digest, absorb, and process the nutrients in the meal. This effect is most pronounced with protein, which requires 20-30% of its usable energy for metabolism, compared to 5-10% for carbohydrates and 0-3% for fats. Therefore, the process of metabolism quickens with additional calories primarily through the increased energy demand of digestion and nutrient processing, and the subsequent storage of excess energy as fat.

Metabolic Rate Changes

Metabolic rate changes in response to a variety of factors including age, body composition, physical activity, diet, and physiological states. It is highest in infancy and declines by approximately 3% per year until age 20, after which it plateaus until around age 60, when it begins a gradual decline of less than 1% per year The rate is directly proportional to lean body mass, meaning individuals with more muscle have a higher resting metabolic rate Metabolic rate can also be influenced by acute factors such as illness, stress, and the menstrual cycle, with BMR increasing during the luteal phase due to higher progesterone levels Furthermore, metabolic adaptation occurs during weight loss, where the basal metabolic rate decreases more than expected from the loss of body mass alone, making sustained weight loss challenging

- Metabolic rate is primarily determined by the body’s need to maintain basic physiological functions such as breathing, circulation, and cellular repair, accounting for about 70% of daily calorie expenditure

- It can be measured under strict conditions as Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR), which requires a person to be at rest, in a thermally neutral environment, and post-absorptive, or more commonly, as Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR) using less stringent criteria

- The metabolic rate is influenced by the type of exercise; while aerobic fitness does not correlate with BMR when adjusted for fat-free mass, anaerobic exercise like resistance training increases resting energy consumption by building muscle mass

- Diet plays a significant role, with excessive calorie intake potentially increasing resting metabolic rate, while fasting or very low-calorie dieting leads to a decrease in metabolic rate

- Metabolic rate also varies seasonally and in response to environmental conditions; for example, migratory birds like the red knot increase their BMR by up to 40% before migration, and animals adjust their metabolic rate in response to temperature changes

- The total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) is the sum of resting metabolic rate, the thermic effect of food, and energy expended in physical activity, with physical activity being the most variable and modifiable component

Factors Increasing Metabolic Rate

Several factors can increase your metabolic rate, particularly your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR), which is the energy required to maintain basic bodily functions at rest. The most significant controllable factor is body composition, specifically having a higher ratio of muscle to fat, as muscle tissue is more metabolically active than fat tissue Building lean muscle mass through regular resistance training and strength exercises can therefore significantly boost your BMR

Regular physical activity, including both aerobic exercise and strength training, increases metabolic rate by building muscle and enhancing overall energy expenditure The thermic effect of food (TEF), the energy required to digest, absorb, and process nutrients, also increases metabolic rate, with protein having the highest thermic effect—requiring 20-30% of its usable energy to be expended during metabolism, compared to 5-10% for carbohydrates and 0-3% for fats Consuming a diet rich in protein can support muscle health and help maintain a higher metabolic rate

Exposure to mild cold temperatures can increase metabolic rate over time as the body works harder to maintain its core temperature Similarly, environmental temperature extremes, such as very cold or very warm conditions, force the body to expend more energy to regulate its temperature, thereby increasing BMR Stress, illness, injury, and fever can also elevate metabolic rate due to the increased energy demands of the body’s response

Hormonal factors play a crucial role; elevated thyroid hormone levels (hyperthyroidism) increase BMR, while low levels (hypothyroidism) decrease it Certain stimulants like caffeine, nicotine, and amphetamines can temporarily increase metabolic rate Adequate sleep, ideally 7-8 hours per night, helps maintain balanced hunger and satiety hormones, preventing a slowdown in metabolism associated with sleep deprivation

Other factors include life stages such as pregnancy and lactation, which increase energy expenditure due to the demands of fetal growth and milk production Growth in children and adolescents also increases metabolic rate due to the energy required for tissue development Eating frequently, particularly including lean protein and complex carbohydrates, can help stimulate metabolism throughout the day Drinking cold water may also slightly increase calorie burn due to the energy required to warm it to body temperature

Thermogenesis in Hypertrophy

Thermogenesis during hypertrophic training refers to the body’s production of heat as a byproduct of metabolic processes, which contributes to total daily energy expenditure and can support fat loss and metabolic health This process is influenced by several factors, including diet, physical activity, and non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT). Resistance training, a key component of hypertrophic training, significantly increases thermogenesis through exercise-associated thermogenesis (EAT) and excess post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC), which elevates calorie burn after exercise as the body repairs muscle tissue and restores homeostasis The metabolic stress induced by resistance training, particularly through high-volume, moderate-to-high intensity workouts with short rest periods, contributes to muscle hypertrophy by causing intracellular swelling and increasing muscle activation This metabolic stress is characterized by the accumulation of metabolites such as lactate, inorganic phosphate, and hydrogen ions, which may stimulate anabolic signaling pathways and promote muscle growth Furthermore, the thermic effect of food (DIT) is higher for protein compared to carbohydrates and fats, meaning a diet rich in lean protein can slightly boost metabolism and support fat loss during a hypertrophic training program Strategies to maximize thermogenesis during hypertrophic training include incorporating resistance training to build lean muscle mass, which increases resting metabolic rate, consuming thermogenic foods like lean meats and chili peppers, and increasing NEAT through daily movement While muscle heating during resistance training has been studied, one study found no clear benefit of supplemental heating on training-induced hypertrophy or strength, suggesting that the primary drivers of adaptation are mechanical tension and metabolic stress rather than heat stress

You must be logged in to post a comment.